This story is about a lady called Phryne, history tells us that she was an ancient Greek courtesan, who ended up as one of the wealthiest women in Greece.

Where was she from?

She was born in Thespiae in Boeotia at around 370BC. Legend tells us that they called her Phryne because she had a yellow complexion like that of a toad! Even though she grew up in poverty, in the end she became one of the Greek world’s wealthiest women.

She was so wealthy that after Alexander razed Thebes in 335, Phryne offered to pay to rebuild the walls. In fact, she even lived to see Thebes rebuilt. She was an interesting lady, they say she even paid for a statue dedicated to herself at Delphi!

The Truth

If we are really honest very little is known about her life and most of the stories about her have been transmitted to us from ancient sources and tablets, which means that sorting fact from fiction is difficult.

Her career as a Model

We are pretty certain that she was the model for two sculpturers of the period Praxiteles and Apelles. A story goes that Apelles saw Phryne walk naked into the sea at Eleusis! He is recorded as saying the sight inspired him so much that he used her as his model when he painted Aphrodite Rising from the Sea. As a reminder Aphrodite was the goddess of love. So maybe Phryne was the ideal model for this, as you will learn later. It was put on display at the sanctuary of Asclepius on the Greek island of Kos, and eventually by the first century AD it became one of Apelles’ best-known works. All because a naked woman walked into the sea!

Then it happened again! This time at the festival of Poseidon, there in front of everyone she took off her cloak and let down her long hair before stepping into the water. Praxiteles was so struck by this that he made a golden statue of Phryne, that we understand was displayed in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. This may have been the first female portrait ever dedicated at Delphi; it was certainly the only statue of a woman alone to be dedicated before the Roman period. The question is, did she pay for it?

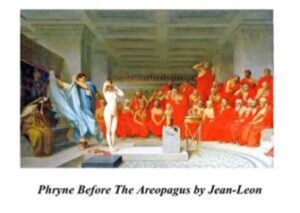

The Trial

Her fame came when in 350 BC she was prosecuted for “asebeia” by Euthias. Asebeia is a charge for the desecration and mockery of divine objects, showing irreverence towards the state gods and disrespect towards parents and dead ancestors

Under these rules Phryne was charged with “asebeia” under three charges, that:

- she held a “shameless komos”, a ritualistic drunken procession performed by revellers.

- she introduced a new god, hryne, to Athens that was named by Harpocration as Isodaites.

- she organised unlawful thiasoi, an event made up pre-eminently of maenads, female companions, and other orgy participants. The maenards name literally translates as “raving ones”.

Now what makes this interesting was that the charges were bought by Euthias, a former lover, and, yes, her defence barrister, Hypereides, was also a lover. She was a lady, who was pretty obviously guilty, but Hypereides defence was very innovative, However, I’m not certain it would work today!

Today, that defence speech survives, only in fragments, though it was hugely admired in ancient times.

Anyway, to finally get to the point Phyrne was acquitted after the jury saw her bare breasts, in fact one writer of the time, Quintilian, explains it by saying “she was saved by the sight of her body“!

It appears that there are three different versions of what happened:

It appears that there are three different versions of what happened:

- Quintilian’s account says that it is Phryne who makes the decision to expose her own breasts.

- Athenaeus’ version claims Hypereides exposed Phryne as the climax of his speech.

- Plutarch’s version says Hypereides exposed her because he saw that his speech had failed to persuade the jury.

Whoever decided to do it doesn’t matter, it worked! She got off and the story has tumbled down through the centuries.

They say that after Phryne’s acquittal, Euthias was so mad that he never spoke publicly again. Then as he didn’t get one fifth of the jurors’ votes, he was disenfranchised, and then he was unable to pay the subsequent fine.

Isn’t history fun?

10 questions to discuss:

- Beyond her birthplace and nickname, are there any other details about Phryne’s childhood or early life available from historical sources?

- What do we know about the artistic styles of Praxiteles and Apelles, and how might they have influenced their portrayals of Phryne in their sculptures?

- The blog mentions various charges against Phryne. Why might these charges have been politically motivated, considering the involvement of her former lover?

- Beyond the acquittal due to exposing her breasts, what aspects of Hypereides’ defense strategy could be considered innovative for its time?

- How reliable are the different accounts of the courtroom drama, considering they come from later writers and may be embellished or dramatized?

- What cultural or social norms in ancient Greece might have contributed to the acceptance of using physical appearance as a defense strategy?

- Are there any ethical concerns surrounding the portrayal of Phryne’s actions and motivations in historical narratives, especially considering the power dynamics involved?

- Do other historical figures, male or female, offer similar examples of using their physical appearance to influence legal proceedings or public opinion?

- How has the story of Phryne been interpreted and adapted throughout history, and how might these interpretations reflect changing societal values or artistic trends?

- What ongoing historical research or archaeological discoveries could potentially shed new light on Phryne’s life and legacy?

These questions encourage critical analysis of the information provided, delving into historical context, legal practices, cultural norms, and the ongoing interpretation of Phryne’s story. They promote further research and exploration of various aspects beyond the blog’s surface-level presentation.

For more on this click on:

© Tony Dalton